Adaptability and the Enduring Popularity of 'A Midsummer Night’s Dream'

From opera and ballet, to Russia (with love) and beyond, the story of 'Dream' has endured and been loved by multiple cultures and audiences over four centuries.

Hello all,

Troubadour is right in the middle of the summer tour for A Midsummer Night’s Dream!

This weekend we are at Vann (Surrey), then Hatch House (hello home crowd!) on 20 July, followed by Cornwall 21-23 July and a final London show on 31 July. I’m really fond of this production and believe its our best for a while so I hope you get the chance to see it!

Recent feedback includes: “Fabulous production last night. Energetic and joyous group of actors. I’m deaf and could hear every word. A rarity in the open air.”

“That’s exactly how Shakespeare should be performed”

“A magical midsummer”

Tickets and all necessary links are avaliable here: https://troubadourstageworks.com/blogs/productions/a-midsummer-nights-dream-book-now

London is a free show (starts at 5:30pm - come along whatever it says on the website) and we’re also opening the Hatch House matinee to all children free of charge. If you’re like to take up that offer get in touch and I will sort it.

To whet the apetite, our programme note on the show below, covering a brief performance history as well as the reasoning behind certain cuts in the adaptation. Enjoy!

Shakespeare is the most-performed playwright globally, and performances outside England started in his lifetime.

A European love of Shakespeare

Members of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men sailed to Antwerp to form touring troupes with other (often international) actors, and then travelled down the great rivers of Europe. Shakespeare was performed in Gdańsk, Poland, in the early 1600s. The financial records still survive!

Rude bits were taken out for court shows… and hurriedly put back in for street performances. This international audience is likely one reason nearly every play includes a fight, a dance, and a song: these scenes transcend language.

Throughout the next 400 years, Europe continued its love affair with Dream. We owe Mendelssohn’s famous ‘Wedding March’ theme to King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia, who commissioned it as part of an 1843 production in Potsdam. Mendelssohn’s music became canon for performances of Dream throughout Europe, with Marius Petipa even including the score in the Imperial ballet adaptation for St. Petersburg in 1876.

Dream was so popular in Germany that when Mendelssohn’s Jewishness made using his music impossible under the Nazi regime Carl Orff was commissioned to rework the music, resulting in Ein Sommernachtstraum in 1939.

Every 10 years brought new European adaptations of Dream:

1949: The French comic opera Puck by Marcel Delannoy premiered in Strasbourg.

1959: The Czech stop-motion adaptation Sen noci svatojánské by Jiří Trnka debuted.

1969: Jean-Christophe Averty brought Le Songe d’une nuit d’été to the French silver screen.

The list of international adaptations is almost infinite and outside of Europe, similar performance heritages exist in their thousands. From Hollywood to Beijing, this story is forever retold, proving there is something in the spell of Dream that speaks to every culture.

Adaptations of Dream on the English Stage

Soon after Shakespeare’s death, the English drama scene was hit by Cromwell’s Puritan Interregnum (1640s-1660), when all theatre was banned. However, Dream continued: the rude mechanicals plot was repackaged as a droll (a skit) by acrobats and jugglers to circumnavigate the ban on drama.

Dream (and theatre in general) returned with the 1660 Restoration, though not everyone was a fan. In 1662, the diarist Samuel Pepys thought it ‘the most insipid ridiculous play that ever I saw in my life’ but admitted there was ‘some good dancing and some handsome women, which was all my pleasure.’ This is the first record of women in Dream’s performance history.

Even without Puritan censorship, theatre makers have always been liberal with the source material of Dream. The play was cut apart every which way in operatic adaptations at the turn of the 18th century.

Purcell debuted The Fairy Queen in 1692, featuring the fairies almost exclusively. In 1745, Frederick Lampe, Handel’s bassoonist, mocked standard theatre conventions in his Pyramus and Thisbe (a comic opera restaging Act V of Dream).

David Garrick, the great 18th century thespian and resurrectionist of Shakespeare plays, sided with Purcell when, in 1755, he brought the original text back to the stage but cut Bottom’s side plot altogether. He called his adaptation The Fairies.

In 1840, actor-manager Madame Vestris staged Dream at The Royal Opera House, unusually choosing to play Oberon. Her production proved so successful that it started a 70 year tradition of Oberon and Puck always being played by women.

It took 130 years for another production of Dream to transform performance traditions so dramatically. Peter Brook’s 1970 production at the RSC, with trapeze artist fairies, a white box and the doubling of Oberon and Theseus and Titania and Hippolyta still influences performance culture today.

Adapting Dream for 2024

Theatre productions are always a chimeric mixture of base text, new creativity and economic reality.

The doubling of the rulers of Athens and the Fairies is the kind of stage convention that has become so standard it seems odd to question (like a female Oberon in the 19th century). The mirror-world reading of the text makes sense, and the pairing of those characters is economical. 50 years on from Brook, theatre economics have transformed. The early 21st-century standard touring troupe of eight is no longer viable for small company finances. Necessity is the mother of invention!

After seeing my fourth Dream (Nicholas Hytner’s fabulous 2019 production at The Bridge, complete with Brook’s doubling and trapeze fairies), I found myself creatively asking… why? Oberon and Titania are the King and Queen of the fairies, so powerful that their arguments upset the very balance of nature. Humans would be beneath their everyday notice. Isn’t it more likely that a minor immortal is meddling? An irrelevant sprite perhaps, who takes delight in causing mischief. Now, where might we find a character like that?

Theseus and Puck

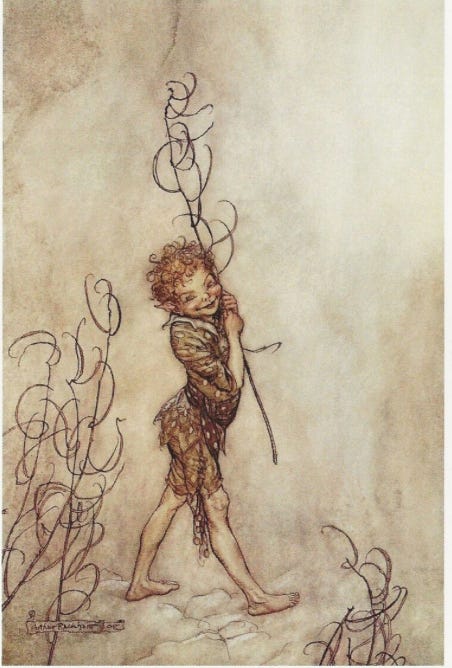

‘That shrewd and knavish sprite Called Robin Goodfellow… Those that hobgoblin call youand sweet Puck.’ (Act II Scene I)

Puck is an amalgamation spirit of at least three folklore traditions: Robin Goodfellow, devils, and the hobgoblin (or brownie). His name likely derives from the Scandinavian and Celtic ‘pouka,’ who would ‘mislead night wanderers.’ His ability to scare horses, change a head to that of an ass and transform into a headless bear are all traditionally demonic powers.

‘Robin Goodfellow’ sometimes refers to a figure in his own right, like Jack Frost, and is sometimes used as a general term for domestic fairy folk, who behave similarly to the brownie. They would help or hinder domestic chores: if offered milk at night, they would ‘sometimes labour in the quern’ or cause mischief by preventing alcohol from fermenting or butter from churning.

Hobgoblin too is a domestic sprite, less malevolent than the standard goblin, known to cause mischief but also grant favours with the cry ‘ho, ho, ho!’ (as Puck exclaims in Act III). In Norse traditions, Santa Klaus was a hobgoblin, which is the origin of Father Christmas’s belly laugh today. Puck and Santa Claus are related—I wonder what the dinner conversation in that house would be?

In every one of these traditions, causing minor disruption and mischief is exactly Puck’s modus operandi. His doubling with the Duke of Athens also provides a way to resolve a problem in the original text. As currently scripted, Demetrius spends the rest of his life enchanted which taints the happy ending. However, we also hear that Helena’s love was not always unrequited. In the first scene, she cries: ‘But ere Demetrius beheld Hermia’s eyne, he hailed down oaths that he was only mine!’

What if Demetrius’ sudden change of affection was not natural but magically induced? What if our agent of chaos, Puck, was so bored with the happiness of the lovers that he decided to stir the pot and set in motion all the events of the play?

This adds a new twist to the early scenes and means that when the enchantment is lifted in Act III, all ‘Jack[s] shall have [their] Jill… and all shall be well.’ Happy ever after is restored for everyone.

The Fate of ‘the Indian Boy’

The final trim to our script involves the ‘little Indian boy.’ His wardship causes Titania and Oberon’s quarrelling, and his inclusion in the story pays tribute to the rich fairy lore of changelings. His Indian heritage is likely more West Indies than New Delhi, and he may have been based on a South American prince Sir Walter Raleigh presented to the Elizabethan court in 1597.

Our change comes in his fate. In the original text, Titania gives him up to Oberon while under the influence of the love potion. It is only after he claims the boy that Oberon releases her from the enchantment. This is a dark side of the King of Shadows: the forced coercion of Titania is not pleasant and raises the question of why he wants the boy so badly. No answer is good, ranging from petulant jealousy to sexual desire. Benjamin Britten’s operatic adaptation of Dream in particular leans into this sinister aspect of Oberon.

In our production, our fairies are more temperamental tricksters than malevolent. Here, Oberon enchanting Titania is intended to teach her a lesson for jilting him, and her release comes when ‘her dotage I do begin to pity’, not when he has succeeded in snatching a young child.

This adaptation has not done a Garrick by cutting out the mechanicals, nor a Lampe and removed lovers and fairies. Our Oberon is less sinister than Britten’s, and our music nowhere near Mendelssohn’s. We nod to Brook with occasional aerial moments and Madame Vestris with our female Puck.

We aim to cut a new five-person path into the Dream of Midsummer.

Costumes and Sustainability

Troubadour Stageworks has an inherently sustainable model of theatre making: no lighting, no sound, virtually no set, and touring rural areas in a seven-seater Vauxhall Zafira keeps the carbon footprint very low.

The origin of our costumes is a bonkers addition to that sustainable story: Oberon, Titania, Helena, Hermia, Snug, and Puck are dressed in upholstery fabric originally destined for landfill. The backdrop fabrics and cloth props come from the same source, and 90% of the costumes are natural fibre to ensure we are not adding to the shedding of microplastics into countryside areas. The vast majority of the rest of our clothes on stage are second hand, actors’ own, or charity shop finds.

Puck describes our players as ‘a crew of patches’ and Snug’s apron is a nod to a time when cloth was so valuable that buying rags was a roaring trade, and everything would be worn to ribbons. If you have attended a couple of our shows over the years, see if you can spot familiar colours—the apron includes fabric not just from A Midsummer Night’s Dream but also Much Ado, Romeo and Juliet, and Twelfth Night!

Troubadour Stageworks is touring A Midsummer Night’s Dream across the southwest and London until 31 July. Book now.